The province’s strengths in biotechnology and biomedicine are “virtually unmatched” in North America, says the minister responsible. Now, a new provincial plan hopes to capitalize on the potential so that sectors such as agriculture can gain from bio-business.

BETTER FARMING – December 2004

By OWEN ROBERTS and HILARY EDMONDSON

No bigger venue exists for biotechnology than BIO, the annual international convention that’s become the industry’s touchstone.

This year’s event, held at San Francisco’s two-million-square-foot Moscone Centre in June, drew 15,000 participants, 900 speakers, and almost 1,500 displays and exhibitors, including a well co-ordinated Canadian exhibit that featured each province’s biotechnology strengths. While those who opposed biotechnology noisily demonstrated outside, most participants staffed their booths and waited to greet visitors as they sauntered by. But Ontario Minister of Economic Development and Trade Joseph Cordiano took a different approach.

Midway through the convention, he invited international media to a news conference in which he proclaimed how the best scientific, academic and business communities from Ontario’s 11 biotechnology clusters, which include Guelph-Waterloo, Hamilton, London, Kingston, Ottawa and Toronto, were coming together “to accelerate commercialization opportunities for new technologies.”

In fact, Cordiano was describing Ontario’s bio-corridor, home to 100 active biotechnology companies, as well as some 2,500 scientists, engineers and technicians. He wanted the world to know that Ontario has invested more than $40 million to foster regional biotechnology clusters through the Biotechnology Clusters and Innovation Program (BCIP) across the industry, developing strengths in environmental biotechnology, life sciences and agriculture in Guelph-Waterloo.

Cordiano figures the bio-corridor and its multiplicity of clusters give Ontario more biotechnology clout and diversity than any other region in North America. There’s some overlap in the regions, but for the most part their individual strengths – and their ability to draw expertise from each other – “makes Ontario’s bio-corridor virtually unmatched,” he says.

He may be right. Expertise in everything from environmental biotechnology, life sciences and agriculture in Guelph-Waterloo, to stem cells and regenerative medicine in Ottawa, to advanced robotics and vascular disease in London, to bio-based products (plastics) and processes in Windsor and Sarnia, gives the province a range of expertise that even major centres in the United States can’t match. Indeed, Ontario has the fourth largest biomedical industry cluster in North America.

But the challenge to the province and others is how to capitalize on all these advantages, and bolster sectors such as agriculture that could benefit appreciably from bio-business. There have been numerous starts to this process, including the establishment of MaRS LANDING, the Guelph-based entity spun off from the downtown Toronto Medical and Related Sciences cluster and designed to link new health or medical technologies (such as nutraceuticals) with agriculture.

The agri-food research community is picking up the pace, too. Driven by the $50-million research agreement between the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food and the University of Guelph, and support for life sciences initiatives from the City of Guelph, researchers are dedicating efforts to a “food is health” program to develop strategies and technologies that connect food and preventive health measures, in areas such as nutraceuticals and the environment.

“By growing and processing nutritious food, farmers and the entire agri-food industry offer a tangible response – one that’s been in effect longer than it’s been political or fashionable – to Premier Dalton McGuinty’s interest in preventive health, such as the challenge of dealing with obesity,” says Erin Cheney, life sciences specialist for the City of Guelph.

Answers on the way

This all sounds fine, and past experience has shown how research can bolster crops and livestock, soybeans, beef and dairy. But when it comes to bio-based products, agriculture has wondered aloud how new initiatives will help. For example, if the farm-raised feedstocks used to create new bio-based products are mostly conventional commodities, such as corn and soybeans, has the industry really gained much, other than a more stable market? And how can the sometimes fractious, diverse and often localized agri-food industry connect itself to individual pockets of biotechnology expertise spread right across the province, and capitalize on new opportunities?

Now, some answers could be on their way, through a plan being created to develop products within these clusters. The regions Cordiano identified in his BIO address have been put under the microscope by his ministry, Ontario Agri-Food Technologies (OAFT) and a consulting firm, NeoBio Consulting, to develop a provincial strategy designed to weave regional biotech interests together.

The fact that OAFT is involved in a major capacity developing the strategy will ensure that agriculture is heard, involved and central to the further direction of biotechnology in Ontario. Participation by all sectors is an imperative for Cordiano, who says the key to success is getting Ontario’s bio-corridor to network and act as a complementary unit, rather than a series of competing regions. “Collaboration is the watch word for this industry,” he says.

OAFT president Gord Surgeoner concurs: “There are significant strengths in each region, and a willingness not only to work towards the development of bio-product opportunities within their region, but to collaborate in building an effective provincial approach to building a bio-economy.” Surgeoner calls the presence of world-class researchers throughout the public sector, both in universities and in government laboratories, “a rich resource that needs to be activated in the direction of bio-products.”

Earlier this year, the bio-products team visited the regions and pored over information submitted to the province for BCIP. Now, it’s drafted what’s being called the Great Lakes Industrial Bio-Products Strategy, a 38-page report being circulated throughout the industry for feedback. The proposed strategy stands to be a landmark program that will give focus to the cluster, direction to the industry, and serve notice that Ontario is serious about bio-products – defined by the province as “materials derived from bio-mass (cellulose, oil, fibre and other agricultural residue) that are not immediately ingested by animals.”

The strategy, as envisioned, is built on the co-existence of agriculture, forestry, chemical, automotive manufacturing and fermentation, and Cordiano’s goal of getting them to collaborate. They’re all well positioned to advance, says the strategy’s authors.

For example, a major North American push is on to substitute petroleum-based fuel and feedstocks with renewable fuels (ethanol, bio-diesel and bio-oil) and chemicals of identical composition, structure and purity, derived from bio-based sources.

BIOX Corporation, a Canadian bio-diesel company, is commissioning a new 60-million-litre facility in Hamilton, which is scheduled for completion in June 2005. The plant will be capable of using 52,000 tons of feedstock, consisting of recovered vegetable oils and animal fats. BIOX hopes to obtain these resources from Ontario farmers.

Scott Lewis, the company’s director of business and development, says it has been able to produce bio-diesel at a cost that will allow it to be competitive with petroleum at the pumps. The provincial and federal governments have been helping to expand this industry by allowing tax exemptions of 14.3 cents per litre in Ontario since 2002 and four cents a litre federally since 2003.

Lewis says government policies and mandates will encourage this industry to grow. The current tax exemption and the federal government’s policy to have 500 million litres of bio-diesel produced per year by 2007 have helped.

“We believe that the projected growth of the bio-diesel industry around the world will be exponential,” says Lewis. “But the highest rate of growth will occur in regions where there is government support, including mandates and tax exemptions.”

BIOX will receive $5 million from Sustainable Development Technologies Canada to help fund this new project and is working closely with National Resources Canada in the research and development stages.

Farm income and jobs

Ottawa based Iogen Corporation an industrial manufacturer of enzyme products from the pulp and paper, textile and animal feed industries, and a leading developer of technology to make clean fuel from natural fibre, says cellulose ethanol is the way to go. The company is putting some weight behind that statement by building the first commercial full-scale plant. It’s scheduled to open in 2007 (even though Iogen hasn’t disclosed where it will be built) and it will be dedicated to cellulose ethanol – a type of ethanol that used agricultural residues such as stalks and husk from corn and wheat straw.

Until recently, creating cellulose ethanol was costly and inefficient, but research and advances in process technology have brought the cost down. “Unlike corn ethanol, cellulose ethanol doesn’t impinge on the food supply,” says Tania Glithero, Iogen’s marketing and communications co-ordinator. “It uses the extras, or leftovers.”

The plant will be capable of producing 220 million litres of cellulose ethanol annually. Glithero says this means more income for local farmers, and an increase in jobs.

Research is continuing into renewable fuel. The Great Lakes Industrial Bio-Products Strategy is calling for a renewable fuels leadership team to be established in southern Ontario and Ottawa. Studies on renewable fuels are now underway at the universities of Guelph, Waterloo, Western Ontario and Queen’s.

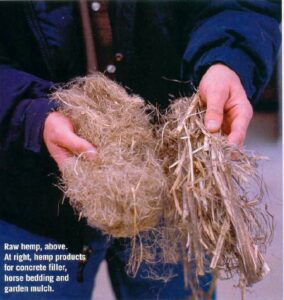

The forestry industry also has the potential to lead an industrial transformation with the provision of less expensive chemicals and cellulose products from wood waste and agricultural residue, corn stover. And the functional fibre industry – hemp, mainly, and flax fibre – is also poised to grow and offer a significant source of value-added agriculture. The single largest use for hemp fibre produced in North America is a substitute for fibreglass, to reinforce the substrate of moulded interior car parts (hemp can reduce weight by about 10 per cent, compared to fibreglass).

When it comes to hemp, Hempline of Delaware, Ont., is in the driver’s seat. Hempline founder Geof Kime helped make industrial hemp (a relative of the marijuana family, except without the active ingredient) a reality in Canada, when he was awarded the first hemp research licence from the Canadian government in 12994. Hempline planted, harvested and processed the first hemp crop grown in North America since the 1950’s. Finally, in March of 1998, Health Canada announced and implemented a commercial licensing system for hemp, so farmers can now grow approved varieties.

Kime has also found ways to use hemp for filler for light-weight concrete, horse bedding and garden mulch. Any use is a good one for Ontario farmers, he figures, because all hemp processed at his plant comes from this province.

Canadian farmers grew 3,500 hectares of hemp in 2004, but with the composite sector estimated to grow by up to 40 percent annually, Kime expects demand to soar. “We are very optimistic about market growth,” says Kime. “Based on the excellent cost and performance of hemp fibre, the demand is continuing to grow.”

Currently, research is being done at universities in Manitoba, Toronto and Guelph to test different ways that hemp fibre can be used. New products are being designed for a range of industries including automotive, construction, furniture and paper.

The major hiccups? The U.S.-led war on drugs, which includes anything that looks like drugs (meaning hemp), and the lack of a further processing plant. Says the Great Lakes Industrial Strategy report: “ We have farmers who are capable of growing the crop, and processors who are building the capacity to separate primary and secondary fibre from the straw. We even have end-use industry interested in using functional fibre in carpets and auto parts. We are missing a commercial retting facility.” (Retting is the process of adding water to the hemp, to isolate the individual hemp fibres).

If a compelling business case can’t be established for a retting facility, the strategy says fibre development in Ontario “will be limited.”

And then there’s the added cost to consumers of bio-products, although Surgeoner says that cost may not necessarily cut into sales. “There’ll be profits,” he says, “if the added value is perceived by consumers as being greater than the added cost.”

Consumers not yet convinced

The strategy’s authors also recognize that each sector has its own problems. For example, opportunities in renewable fuel manufacturing are constrained by production inefficiencies inherent in any industry in its infancy. Feedstock costs can be high, although, they’re starting to look reasonable, as oil hits $50 a barrel. And end-user motivation is lacking; when it comes to “bio” anything, the industry still hasn’t convinced consumers what’s in it for them. The lack of a commercial enzyme treatment facility is constraining progress in functional fibre. And forestry is constrained by investment capital, as well as the lack of security of feedstocks and end markets.

OAFT’s Surgeoner believes added value can take the form of increased product life, such as composite lumber decks and fences, or decreased weight, like composite bio-plastics used for auto parts, where decreased weight creates value by increasing fuel efficiency. He and the rest of the bio-products team also realize product development takes money, and they’re recommending a self-sustaining, $10-million commercialization fund be created. Such an Ontario Bio-Products Seed Fund would partner with existing federal funds.

“We’re proposing the creation of a fund that will stimulate the creation of additional funds,” the report says. “The government cannot afford to stimulate the development of an industry, nor is it appropriate that the government pick individuals opportunities to nourish. A middle ground must be found where the government can provide the impetus to stimulate an entire industry in partnership with the industry, and in partnership with private capital.”

As an example, it cites the need to encourage specific investment in developing enzymatic functional fibre processing facilities in Ontario to stimulate the bio-fibre sector growth.

But the report’s authors say it’s not financial or technical problems that will ultimately determine the bio-products strategy’s fate, but public acceptance. “A bio-product opportunity may make all the sense in the world, but still face constraints that an equivalent innovation within the existing industry would not face,” says the report.

“We need to build trust and comfort across communities. We need to build trust for the introduction of novel bio-product opportunities within the investment community. This same level of trust needs to be built within the decision makers of end-use industry.”

At the end of the day, though, these end-users report to consumers and consumer acceptance is still far from assured. While increasing numbers of Canadians have become familiar with biotechnology, they say they still don’t want to see it on their plates.

A Decima Research poll released right after BIO last summer found that the major concern about biotechnology continues to be its risk, particularly long-term risks to health and to the environment, of genetically modified food. By a six-to-one margin, respondents said that the benefits of new technologies outweigh the risk, that the benefits will be even greater in the future and that they’re willing to accept some risk if there’s a health benefit involved.

But when it comes to food, just 63 per cent agreed with accepting some risk to develop new biotech foods that contain vitamins or medicine. And only 55 per cent said they agreed with using biotechnology to help farmers use fewer pesticides in corn.

Clearly, there’s a long way to go in winning consumers’ hearts.